Reflections on the Golden Age of Backpacking (late 2000s-early 2010s)

Backpacking in the early days defined how I think about travel, and how I long for the days of no smartphones, meeting people in hostels and enjoying the simple life. Here’s how backpacking is different now, from what it once was.

This article may contain affiliate links. We earn a small commission when you purchase via those links — at no extra cost to you. It's only us (Becca & Dan) working on this website, so we value your support! Read our privacy policy and learn more about us.

It probably goes without saying that “backpacking” is a different world now, when compared with the roughing and grunginess of what the term originally meant for me.

My first time backpacking (in the true sense of the word) — going with only a backpack and no plans (!) to Southeast Asia when I was 20 — was such a pure backpacker experience. The Internet was not something that defined the world (yet) in those years, and because of it, many places were still more authentic and not “made for Instagram.”

For many years now, I’ve wanted to reflect properly on how backpacking made me into the traveler I became and have become. Read on, for some fond memories, reflections and good stories.

How was the golden age of backpacking (before social media and smartphones) different from backpacking now? Read on, and enjoy the photos.

The world was less connected

The Internet, Google searches and social media have made everything available. All the time. Very easily. With just hitting “Enter.”

For me, backpacking in Thailand, Malaysia, Bali, Laos, South Korea, China and Japan in 2009 meant that these places were authentically Thai, Malay, Balinese, Lao, Korean, Chinese and Japanese. Social media hadn’t brought things like American dance crazes and trends to East Asia, and vice versa, sensations like K-Pop hadn’t exactly made it to the West.

Every time I went backpacking somewhere new, I really didn’t have so much of a way of learning about it, except for reading travel guidebooks. Sure, the Internet existed, but it wasn’t full of hi-res professional imagery, long-form vlogger YouTube videos, TikTok and Facebook reels or Instagram stories. You just went, and figured it out.

Because the world was less connected, you could travel somewhere and there were fewer comforts of home. This made it feel a bit more legit — that you couldn’t just get what you’d get at home, somewhere far away like Kuala Lumpur or Beijing.

You also had to really enjoy what was in front of you, because you couldn’t find it at home. No way. Northern Thai cuisine? Better enjoy it in Northern Thailand. Tank tops that said “Vang Vieng, Laos?” Better grab one while you’re there, because you couldn’t order one online.

Traveling and really feeling like I was far, far away from home without a way to Whatsapp my parents from a night bus at the Cambodia-Vietnam border made things feel more removed, and therefore, more special.

You’d go without a plan

The first time I went to Thailand in early 2009, I was 20. I was studying abroad in Hong Kong with other 20-year-olds, and it was the Europeans who knew “how to travel well.”

I told my mom I was going to Thailand with no hotel reservations and no itinerary, and she insisted that I make both.

“No, you don’t understand,” I said, and honestly, neither did I. “These friends know what they’re doing and they said it’ll be fine.”

“Fine” was a loose term, because we landed in Bangkok at night, and walked up and down the 2009 version of Khao San Road (if you’ve been there, then you know) asking if each guesthouse had availability. As a side note, this was the first time I saw a dead cockroach.

A few of us piled into a guesthouse room that had no windows, and the next morning, we ate breakfast on the roof deck, beside little pools of water that had lily pads and flowers. I couldn’t believe this was my life.

The trip got weirder, though. We took a very unglamorous Thai train (where I had the pleasure of seeing what baby cockroaches look like) from Bangkok down to the train junction town of Surat Thani, where we then hopped ferries to the Thai islands. The European friends “still knew what they were doing.”

We didn’t stay in the “it” town of Koh Phangan; instead, we took jeeps and pickup trucks at night from the ferry dock to a remote village that had a beach dotted with 3 guesthouses and 1 restaurant. I just came across a photo of the nearby waterfall in my old photos, Googled it, and found that the beach was named Haad Sadet Beach หาดธารเสด็จ.

We stayed in something that resembled a treehouse, and then the rest of the nights, we stayed in open-air bungalows built on top of rocks along the water. (In my Google search for this article, I found that it was the “Mai Pen Rai Bungalows,” and it’s coming back to me now as well that Mai Pen Rai means, “It doesn’t matter” in Thai.)

It was idyllic. And remote. Because there was no Google Maps and because the Internet Cafe’s Internet seemed to be down for about three days, I had no idea where I was.

You’d bring along a travel book or paper map

I landed in Shanghai, China, as a first-year English teacher in August 2010, with a Blackberry that had no data plan and a paper map of the city.

I would carry my map around in a purse, and use it to turn left or right on streets in new neighborhoods, starring where my friends lived, where my favorite shops were and where to get food. Within a few months, it was tearing at the seams, but I needed that map. It was my lifeline.

My favorite books from 2009 (and still to this day) are Lonely Planet guidebooks. A book that still lives in my LP collection is a Vietnam travel guidebook from a hostel that had a book shelf in Vang Vieng, Laos. It’s actually a fake Lonely Planet book — and what this means is that it’s a photocopy of an original.

Regardless, when transversing a new country and in the days before widespread Internet, having a trusty book was a foundation for a good trip. Arriving in a new city? Check the book for where to stay and where to eat. Going onward? Reference the “Getting there & away” section to find out a loose timetable of bus or train times.

There was no website where you could get those things in 2009, or even if there was, I didn’t have a smartphone to access it, and I couldn’t sit for hours in an Internet cafe, or I’d be missing the best parts of the trip: living it.

You’d look for an Internet cafe

The night I got to Vang Vieng, Laos, someone else and I were split up from the rest of the group, who had all arrived earlier. Because none of us had enough cell phones or SIM chips among us, we had no idea where our friends were staying. The plan was loosely, “I’ll leave you a message on Facebook, and hopefully you’ll find a way to check for that.”

In what might’ve been the final hours before the town’s Internet cafe closed, we were able to hop onto desktop computers, checked Facebook and found that our friends had left us the name of a guesthouse where they were all staying. But we had to find where that was.

In an unbelievable moment of fate, as we left the Internet cafe and were wandering, we ran into them — the whole group of friends from our university in Hong Kong, and it was a clamorous occasion.

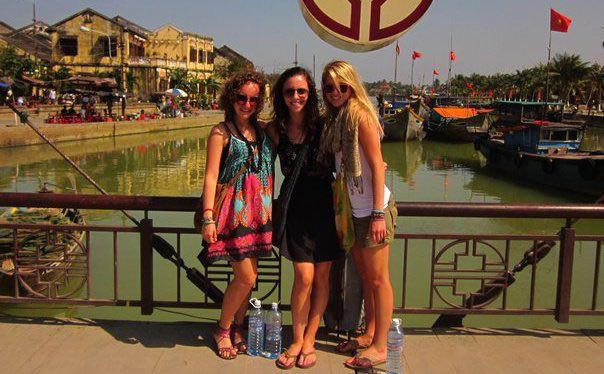

On my trip to Vietnam two years later in 2011 with my friends Emma and Alyson, my friend Emma had a smartphone with data. I remember sitting in our hotel in Hoi An asking if I could send an email on it. It was thrilling to not need an Internet cafe to do that.

You never would’ve sought out Instagram moments

Instagram was something I downloaded on my iPod touch in 2011. It was an app that had 8 or so vintage filters, and you’d open the app, take a photo and it would look “old” or “vintagey.” I took a few photos of my friend Steph at a cafe in Shanghai, I took photos of people hanging their ducks and chickens on the street for poultry season and I took a few photos on Instagram in the Shanghai metro.

There was no real posing for a photo for thousands of people to see it and click “Like.”

In 2009, my study abroad friends went on that Southeast Asia bender, and among us, someone had “the good camera.” Wait, I think it was actually a disposable camera, and in my mind, the photos were so good that it didn’t matter what kind of camera it was.

Our moments were captured on film while we were jumping into the river in Vang Vieng, Laos, and posted on Facebook in an album that let us all tag ourselves. The photos never made it to Instagram. They were just for us, for the group and for the memories (OK, and they were posted on Facebook, which is where I still look at them).

I didn’t stay in hostels nor did I go to famous places to take a photo that would be a magnet for lots of “Likes” and attention. I backpacked in Asia as a twenty-something to take good photos that made me feel challenged. They were photos that I wanted to show friends and family back home. I posed with a few landmarks, did a peace sign with my right hand and wound up with accidental photos that are still to this day, “the good ones.”

You’d get a local SIM on a dumb phone

Living abroad in China as a twenty-two-year-old made me scrappy and street smart. I had a phone number from my Chinese SIM card that was so long that friends back home joked that it was a credit card number. It was 11 digits long.

So when I landed in Cambodia in 2011, I picked up a local Cambodian SIM card for my brick cell phone in order to text my friend Jayson, who was in my study abroad program in Hong Kong in 2009. Naturally, you’d get a new phone number. Naturally, you’d use it for six or so days, until you went onward, and for me that was to Vietnam (where I’d get a local Vietnamese SIM phone number).

Getting a local SIM was the only way you’d crack the code of getting cell service, because I didn’t know of any way to get international cellular data (like Google Fi) between 2009 and 2011. “Data” wasn’t even in my vocabulary at the time: who needed it? Apps didn’t really exist, and smartphones were just beginning to catch on.

Getting a local SIM unlocked ways to do things like call your hostel if you were running late and wanted them to save your bed reservation in the hostel dorm room. Getting a local SIM let you text the laundry service that might be laundering your dirty clothes in northern Thailand. Or maybe not. It was hard to tell who even had a cell phone.

Life was simple.

You’d actually make friends in hostels

That’s right: the best friends I’ve met in hostels were earlier on in my backpacking days.

There was Genevieve, who I met in Pingyao, China, in 2012, and who later visited me in Brooklyn, NY, in our thirties. There was Shahak, who I met in a hostel in Nicaragua, and later grabbed brunch with in Tel Aviv, years later, on a business trip.

I met my friend Sophy in a hostel in Panama in 2012, and there were the Australians I met in Harbin, China, earlier that year, who made me feel like I had friends when I was traveling solo.

I met my friend Doreen in a hostel (or was it a restaurant?) in Monteverde, Costa Rica, and she later (wait, this is a good one) hung out with my NYC friends and then married my friend from college. We still trace our roots to that trip, when we walked in the rainforest and then met up again in Panama, where we made the most epic group of friends that felt like family.

It was on that trip in Boquete and Bocas del Toro, Panama, when I met my friend Mark from Scotland, who (a decade later) would visit me and Dan in our Brooklyn apartment and take us to a party on a yacht (where he worked) parked in the Manhattan harbor.

My hostel friends from my early travel years are incredible.

The friends I’ve made in hostels have been real buddies. We’d keep in touch after we left those hostels, whether it was together, for a new destination, or apart, and via Facebook, for years afterward. They saved my sanity when I was on my own, or made great additions to groups of travel friends that already had formed.

You’d put your full trust in locals, and really, anyone

My friend Greg and I went to the Philippines for Christmas break in December 2010. He said we could hang out with his friend from Manila, who he knew from his grad school in Taipei. I didn’t have plans, so I was game.

I came from China, and Greg came from Taiwan, and we met up, erm, somewhere, in Manila, the Philippines. It must’ve been the airport, because I don’t think I knew much about WiFi and I certainly wasn’t going to have a Filipino SIM card when I landed.

Greg and I had a Shanghai-Taipei call before we both booked the trip, and I remember looking at a pretty rudimentary website for a hostel/guesthouse in Manila that we booked for the duration of the short trip. I suppose we were able to figure out that it had good reviews, so we booked dorm beds.

On Christmas Eve, we spent the night with Greg’s friend’s family, which was incredibly kind and generous of them to have two Americans for the most holy night of their year. As the night grew longer, all I remember is that Greg’s friend’s brother, or cousin, offered to drive us to a volcano in a crater, which had a volcano and a crater. Or something.

You can’t make this stuff up.

Passed out in the backseat of their car, I’m recalling that we went in the middle of the night to see the Taal Volcano Crater Lake, and I still have no idea why it was smart to do this at night instead of during the day.

Regardless, we trusted the idea, because we had nothing to lose.

Hostels were basic

I once stayed in a two-person dorm room at a hostel. Yes, you read that correctly: I stayed in a room for two people, but we were random strangers, so it was like staying in a private room with … a stranger.

Not all hostels were this weird, but you did have to roll with the punches as a backpacker in the late 2000s and early 2010s. Staying in a dorm room for anywhere from 4 to 20 people was just a fact of life as a backpacker. It would cost you just a few dollars in Southeast Asia. I even stayed in a private room (albeit a room with bunk beds) with my friend Jenna in Chiang Mai, Thailand, and I think it was $3 each.

Not only were hostels basic, but it was normal to stay in a basic hostel in Southeast Asia that had fairly acceptable reviews as long as everyone was able to get some rest and maybe a free breakfast in the morning. In Southern China, I stayed in a 4-person hostel dorm for $5 per night, and the prices roughly remained the same among China and the rest of Asia (save for South Korea and Japan) at the time.

You could also find people holing up in hostel dorms for many days or weeks at a time. This was the expert backpacker style. I think it was in Manila in the Philippines where the people in my and Greg’s dorm were backpacking strongholds who just didn’t feel like leaving the place.

Hostels didn’t have mantras written in neon for a social media moment, and they certainly didn’t have coworking spaces or free WiFi that caused anyone to be glued to a screen. In fact, the hostel common area was often a place where people went for the very reason of meeting others, and starting out on an adventure together.

The hostel kitchen would be a place I’d go to for making meals with others and maybe chatting up a storm while washing dishes.

Today’s hostels are tough competition, with glamorous Instagram followings, luxe accommodation options and more ways to seclude yourself, with your phone or laptop. There’s a lot to know for how to book a hostel, and it makes me a little sad that it’s not as easy to be a young person trying to disconnect from the demands of home, but it makes me happy that it once was this way.

You’d enjoy the simple backpacker life

The most “simple” times in my memory from the really early years of my backpacking were in Laos with that big group of friends I mentioned. The three or so days we spent in Vang Vieng in April 2009 (before the crowds and tourists destroyed it) were blissful.

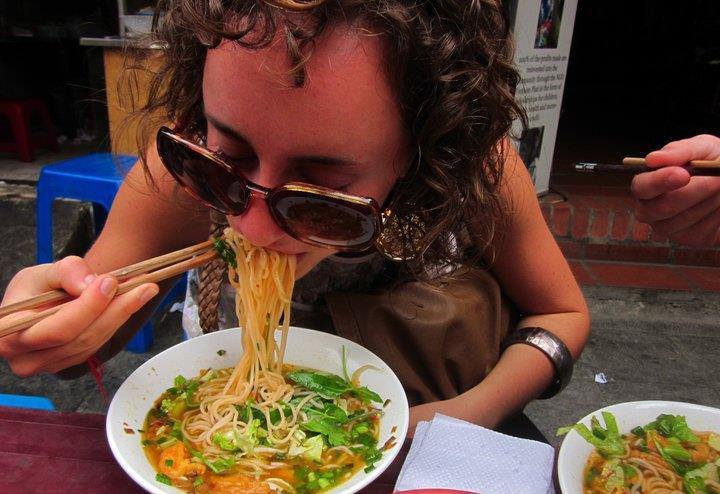

We rode motorbikes. We took walks in the river at a mulberry farm next to families doing their laundry with their kids wading around. We drank smoothies from the street (which is how I learned about really bad travel food poisoning and what spurred me to write how to avoid getting sick while traveling). We ate noodles at cafes that only showed repeat episodes of FRIENDS on TVs mounted off the ceilings.

In early 2011 when Emma, Alyson and I went to Southeast Asia for my fourth time already, we took an 8-hour boat ride from Phnom Penh to Siem Reap. Why? It would be an experience. Would a flight have been nicer? Yes, but it would’ve cost a bit more, and we were trying to travel for super cheap. Was this an experience? Yes, it sure was.

We sat on the edge of the boat, riding north in a country that was new to us. We were on a boat that only backpackers traveled on, with a “bathroom” above the motor where you could use the facility for the time you were there.

No one was sitting around glued to their news feed or to Twitter/X or answering emails, because the average backpacker didn’t own a smartphone and because there was for sure very little signal. It was better that way.

The glory days of backpacking

The last time I really “went backpacking” was my and Dan’s trip to Myanmar. I say that because we went with backpacks, we didn’t have a baby yet and we stayed in hostels. Yes, really! As a couple who would be married one year later, I was still insisting that we stay in hostels, even if it was privates.

It was all for the “backpacker” stamp that I might as well have on my arm.

Backpacking is different, now, though. In Inle Lake, Myanmar, I sat with my laptop, checking into my work email, lamenting that the Internet was just a bit too slow to do much.

We didn’t make friends with anyone else on that trip because we traveled as a couple, stayed in our private room, had WiFi everywhere we stayed and went to bed early most nights to get up at the crack of dawn and take photos for the website you’re reading right now.

The days of my local SIM chips, dumb phones, dorm rooms and solo travel are over. It’s bittersweet that the days of paper maps no longer exist (Google Maps is just too functional!) and that in the back of my mind, I do often travel for excellent photo opportunities that I aim to share with our audience of thousands of readers.

I smile, though, because nights like those ones in Bangkok and Siem Reap are a part of who I am, and because the golden days of backpacking were awesome.

📓 Thanks for following our story

We use this corner of the site to share milestones and lessons from life on the road. If you're enjoying the peek behind the scenes, a coffee keeps us caffeinated to do more.

Keep the stories comingYou may also like

-

![A group of people posing for a photo in a coffee shop.]()

GOAL Traveler X Half Half Travel Podcast

We were delighted when Cyd and Marc of GOAL Traveler invited us to be interviewed for their travel podcast. We discussed our experience traveling as a couple so far as digital nomads with Remote Year. We talked about our favorite travel packing hacks, along with our favorite destinations and best tips for traveling long term.

-

![A man standing on top of a mountain in the philippines.]()

@germanbackpacker: Building a Bilingual Travel Blog

Patrick from @germanbackpacker is one of our favorite bilingual travel bloggers who has built a dual-language blog and travel website. Check out his thoughts on building content in English or your native language.

-

![a person sitting on a rock next to the ocean]()

Authoring the Pride Atlas: Interview with Maartje Hensen

In this interview with Maartje Hensen, learn about how the Pride Atlas, a queer traveler’s guide to the world, came to be, as well as the experiences that led to the project.

-

![Two people standing on a road with mountains in the background.]()

Carlie & Pat: Off-the-Beaten Path Van Life Travel

What's it like to take a big trip as a couple in a campervan? Carlie and Pat of @verynicetravels told us how to do a 'van life' trip across Europe, and how to deal with unexpected turns during travel.

-

![a woman standing in front of a blue and yellow building]()

Why Traveling with a Baby Is a Whole New Game

I never knew that traveling with a baby was as different as it really is, from traveling as a couple before kids. Here, I compare the needs of family travel versus my travel life before becoming a parent.

-

![A bearded man wearing a grey t - shirt holding a cup of coffee.]()

Adam’s Coffee: Exploring Travel through Coffee

Ever think about traveling around the world for coffee? Our friend Adam started his Instagram to combine his love for coffee and travel. In this interview, he’s sharing how it all began.